Note: The following transcript is created by both humans and AI, so despite our best attempts may contain errors.

Bull: And today is Wednesday, December 27th, 11am Eastern Standard Time. This is Brian Bull, lead interviewer and director of the Public Radio Oral History project. And today, our guest is Terry Gross, longtime host of NPR’s flagship talk program, Fresh Air. She and the program have received many awards and distinctions, including the Corporation for Public Broadcasting's Edward R. Murrow Award, a Peabody Award in 1993, and an institutional Peabody Award in 2022. On top of that, Fresh Air was inducted into the Radio Hall of Fame in 2012, and Gross received a National Endowment for the Humanities Award from President Barack Obama in 2015. Gross has also lectured at several prestigious colleges and universities, and has even made cameos on The Simpsons and the NPR quiz show, Wait, Wait, Don't Tell Me.

Terry Gross, thank you so much for joining us. It’s a genuine pleasure.

Gross: Thank you. I'm glad you're doing an oral history.

Bull: Some basic biographical information first, please. Terry, when and where were you born?

Gross: I was born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1951.

Bull: And is it true also that you had a very brief stint as a middle school teacher?

Gross: Yes, and it is especially true that it was very brief.

Bull: Middle school is not a pleasant experience for anyone, really. So I applaud your bravery, however brief. I believe your earliest experiences though in broadcasting were as a volunteer at a campus station at the University of Buffalo way back in 1973. What kind of person was Terry Gross back then?

Gross: So I was somebody who was looking to find work that I would love, and after - I never felt called to teach, but I was an English major. So what are you going to do? So I got placed in a very tough junior high school, and I was not really prepared for that, and I didn't do well. I was fired. The kids wouldn't stay in the room. I didn't know how to be an authority figure. I was used to defying authority figures, not being one. This was in… 1973? And so it was a mess. I got fired, which was a lucky break, and then I kind of stumbled into public radio.

Bull: Had your parents always pushed you to be an educator of sorts? Or what were their expectations of you as you're growing up?

Gross: Well, when I was growing up, I think my mother expected me to be an executive secretary, because there weren't many options for women when I was growing up. And she had been a secretary, and she was, I'm sure, an excellent one. She knew stenography, she was an excellent typist and very smart, but you know, there weren't really a lot of options for her. She went to high school, didn't go to college. Ditto with my father, which was not uncommon that, and especially for the children of immigrants, which my grandparents were on both sides. Yeah. So that was for the expectation.

And when I started in public radio, it was so new and so unestablished they never heard of it, and they kind of didn't believe that it was anything real, or that I could, you know, really have any place in it. And when they found out that it was real, and when especially when the show went national, they were just overwhelmed. They were so happy.

Bull: You defied their expectations, I'm sure.

Gross: Yeah, well, you know it was a different world, though. Public radio was brand new.

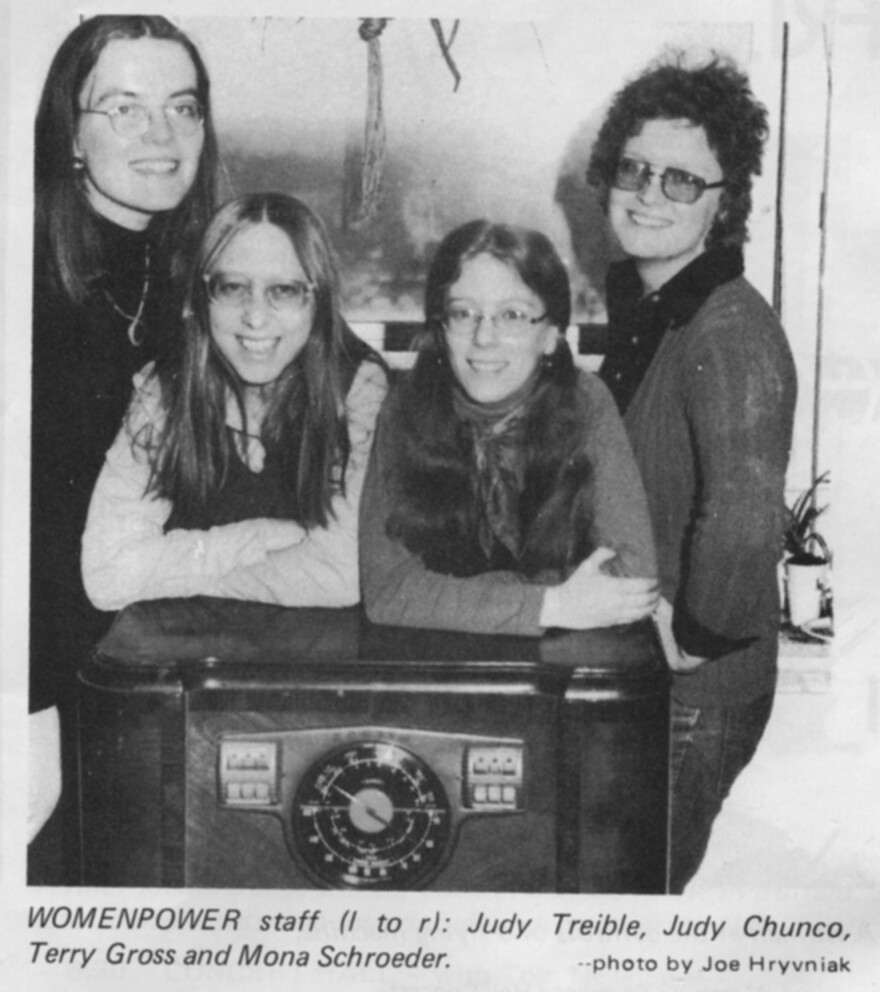

Bull: Yeah. In fact, I believe that the show that you had worked on early on, as you were just getting started, was a local feminist program called “WomenPower”, and then you got involved with “This is Radio” as it was called. And back then, it seemed to be a very locally driven program, and maybe more fit into the mold of what we consider community radio today?

Gross: It was a college station, so it was college radio. It was college radio in the early days of - of NPR. So it was, it was a wonderful - it was just like a creative explosion. There were all these, like, smart, funny, creative people were coming from many different directions, like blues, rock, jazz, news, women's rights, gay rights. It was a very exciting place. Oh, classical music, it was a very exciting place to be. I learned so much working there, not just about radio, but about, like, music and history. And it was, it was, it was thrilling, really. And I was for a while, the music librarian, so I got to go through all the new records that came in, and I was able to learn so much about music doing that.

Bull: Back in the day, when they were still vinyl LPs and eight-tracks.

Gross: Oh, no, exactly. Yeah, it was way before CDs.

Bull: So what were your earliest influences as an interviewer? Was there someone that you were inspired by who maybe had their own program, either on radio or television, or someone you read about in the papers that you know you looked at and said, “Hey, I can do that job. I'd be willing to be an interviewer myself”?

Gross: Well, I hadn't actually listened to that many interviews. I was pretty new to listening to public radio, and I fell in love with that. I had a job typing, almost fulfilling my mother's expectations. I was typing a faculty policy manual at Buffalo State College, which wasn't the university. It was nearby, but it was a different - a different college, and what I would do is leave on WBFO, the public radio station in Buffalo at the time, and I heard so much great music and interviews, and I thought, God, that would be so great. But I didn't think I could do it. I didn't think there would be a doorway into it.

I had decided I wanted to be in media, but how do you get into media? So I thought, well, I'll take like, enroll in a graduate program in media. And then I realized those programs, the ones I found were mostly like educational programs for teachers about how to use, like mimeograph machines and like little films for the classroom and stuff like that. And I thought, like, that's not really what I want. And then I had a roommate who had a girlfriend who was on public radio and was leaving the WomenPower show. So there was an opening on that show, and my girlfriend, my friend whose girlfriend was leaving WomenPower, gave me the phone number of one of the producers, and that's how I started working on the show.

Bull: Was it kind of a natural thing for you, or did you have your earliest bits of “crash and burn and learn”?

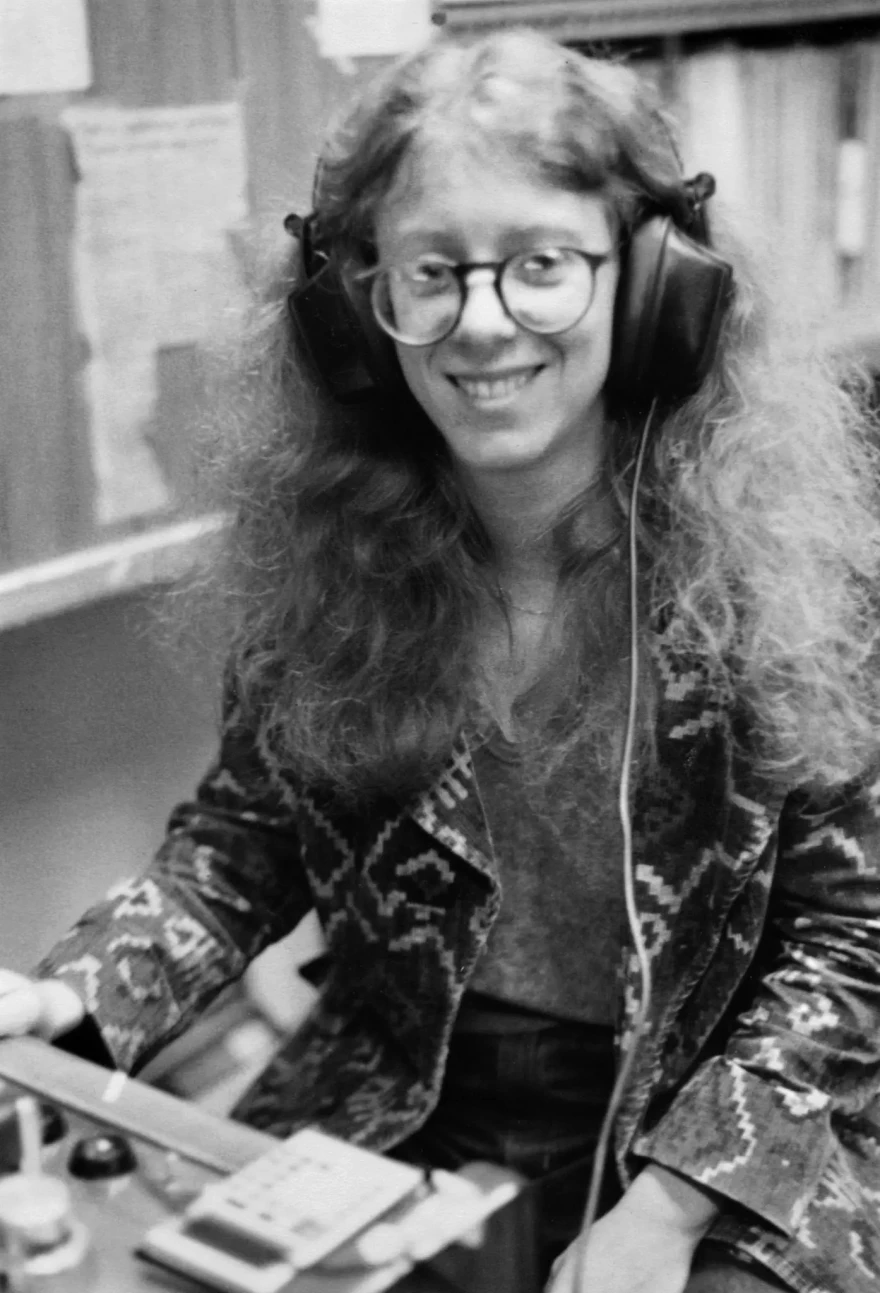

Gross: Oh, crash and burn and learn. But it was exciting. It was thrilling, really, to create radio. It was like magic. You turn a knob, your voice is on the air, or someone else's voice is on the air. You know, I learned how to engineer because we weren't the union shop. It was a college station, and I learned how to edit tape and mix. It was wonderful.

Bull: Back in the days of reel to reel and razor blades and –

Gross: Reel to reel. And yes, all of that, all of that. And it was exciting to learn on a feminist show because it was very connected to what I was going through at the time, which was, you know, discovering feminism and rethinking a lot about my life and about my relationships. And it was all revolving around that radio station, we - we'd stay up for 24 hours sometimes, just like meeting our weekly deadline, trying to make it good. And when it wasn't good, the people at the station would let us know it wasn't good enough. There's a lot of peer pressure to do your best, and if your best wasn't good enough, there's a lot of peer pressure to just give up.

Bull: And you kept going, it sounds like you incorporated the feedback and began making a name for yourself. One of the names that I keep coming across as I work on this project is that of Bill Siemering, who founded the principles for NPR, and I believe, had a history himself there at WBFO. He was trying to get more voices, more diverse and underrepresented voices, onto the air back then. And do you have any immediate recollections of working with Bill?

Gross: Oh, well, I missed him in Buffalo. He left before I got there. But one of the memos he wrote, and I don't even remember what it was about, was so inspiring. It was still on the wall and remained there. I don't know how long it was there after I left, but it was there a long time. Then he went to another station, and then ended up coming to WHYY which is how I really got to know him. And he was so wonderful to work with, and he's a dear friend today. We just, we were, you know, we became actual like friends, as opposed to colleagues, after he left. And I just love talking with him.

To get back to your question, about interviewers who inspired me? So when I started interviewing, I was at WBFO in Buffalo, and I used to listen to the CBC a lot, the Canadian Broadcasting Company, and they were doing fantastic radio. There was a show in the morning called This Country in the Morning that was hosted by Peter Gzowski, and a show in the evening called, As it Happens, which I think is still being broadcast.

Bull: I still hear it on air, yeah.

Gross: Yeah. And they were - both shows had real different styles of interviewing, but they were informed and casual at the same time, no matter who they were talking to, whether it was a head of state or a comedian. And that I found that inspiring, to be formal, to be informal, but informed at the same time. I love that.

And of course, Susan Stamberg, you know, inspired me, as she inspired everybody in radio at the time. And then people like, Dick Cavett, because he would ask anything, and he'd even say, “Here's something I'm thinking, I don't know what the question is.” And I think he gave me permission to confess that on the air that “I'm not quite sure what I want to ask you, but it's something like this.” You're “I don't know what the question is, but here's what I'm thinking.” I got - that was very helpful to see that. And he'd get such interesting things out of people that other interviewers probably wouldn't.

And then as time went on, I was inspired by Ira Glass and the way he spoke to people, and a lot of other people at NPR, but also people like Ted Koppel. Not that I aspired to be Ted Koppel. He's a news guy, and I'm really not - I do - I interview a lot of journalists, and I really try my best to stay on top of the news. But he, he was just a professional news guy and, you know, but I thought he was great.

Bull: No, there's a lot of outstanding examples there. And one thing I really appreciated too, about your style, Terry, is that you don't have this self-important, stodgy, authoritative tone to your program. It's very casual, very comfortable and also very unpredictable. Because I think, as you've also mentioned in your book, All I Did Was Ask is that there are some guests you have who come on who think that this is going to be a standard media junket - a PR junket - where they basically give you pre-scripted answers and bullet points that a marketer has already approved in advance. And sometimes you just kind of get –not necessarily under their skin – but you get them probing things that they weren't necessarily prepared to talk about.

And I think that's what makes the show very captivating and fresh for a lot of people, is that it's not predictable, and it's not what they've heard on X number of other media outlets. So you obviously have made it your own style, but also you draw upon some really great influences.

Gross: Yeah, I had some great influences, you know - and what I love about now is that, although podcasts are creating a lot of competition for public radio in general, and for our show, there's so much good stuff to listen to now. It's like an abundance of riches.

Bull: Fresh Air became an NPR program in 1985 which means, hey…your show's gonna be 40 next year.

Gross: Nationally – we actually have two anniversaries as a national show. In ‘85 we were a weekly half hour show on NPR, while we remained a daily local show. And then in ‘87 we went daily national on NPR.

Bull: Well, congratulations. That's amazing. And the show itself, Fresh Air’s earliest roots went back to 1975 correct? When you moved to –

Gross: Yes. Well, the show preceded me, and then I changed it when I got here. Before I got here, people used to sign up. There was a host that people would also sign up to do interviews. And the music in between was mostly classical music. And I remember when I got here and I played mostly jazz rock and punk and blues, R&B on the show in between interviews, some listeners got really upset, because we were largely a classical music station then. This was a long time ago when NPR only had like a few shows to offer to local stations.

Bull: You were agitating the “blue-haired grandmas” in the audience.

Gross: Well, I don't want to stereotype or disrespect classical music listeners, because classical music is beautiful, and I love a lot of it. I'm just not terribly informed, and it was before I started to fall in love with opera, so I was completely uninformed about that. But it's not the show that I would be capable of doing.

Bull: It also sounds interesting too, that there was a sign-up list for interviewees, and I –

Gross: That's what I'm told, because I wasn't there before I got there, if you know what I mean, but it was a very free form show.

Bull: I was going to ask you a little bit more on that. What were those earliest years like for you? As you mentioned in the broadcast and you took on the program, the name change followed, and I assume that you became more measured and selective in who you interviewed, correct?

Gross: Well, and see the show I did in Buffalo was called This is Radio, and it also connects me to the aforementioned Bill Siemering because he created that show during the campus uprisings during the Vietnam War, when there were all the protests, and the police and the students did not have a good relationship. There was tear gas, there was police batons. People got injured, and what Bill tried to do was create a show that would be a safe space for people you know, like administrators from the university, students, I think police as well, to come and tell their side of the story, because the newspapers and the TV stations weren't really getting it right. And also the students were sometimes not letting the you know, the president and vice president of the university to speak, they get kind of shouted down.

So that's how This is Radio was created, and then when the campus quieted down, it became a three-hour interview in music magazine show, which I eventually co-hosted. So that's my first connection to Bill.

Anyway, so I did that show for a while, and then Fresh Air was created by the former program director at WBFO, and he wanted to create a magazine kind of format, similar to what This is Radio had become. And then after that was on the air for a year or two, probably two, the host left and there'd been a couple of hosts, but the - the host, who was hosting at the time left, and I was hired to take over.

Bull: And did you feel ready to take over?

Gross: You know, I loved Buffalo - I loved WBFO so much, and I missed it so much when I got here, because this was a much more quieter, small staff, classical music station, as opposed to, like the sometimes like just the variety and the creativity and the mix of tastes and styles at WBFO. But it was a - it was a real job with - with an actual salary, and I got, I got a whole lot of freedom.

And then three years later, when Danny Miller came to the show as an intern because he was in the radio TV film program at Temple University, that's when my life really started to change in Philadelphia, because he became from an intern, he became an associate producer, then a producer, and then executive producer when we went national, and we've just been like radio partners like since 1978 and everybody should be so lucky to have a working relationship and friendship like we do. It's been a mainstay of my life and my career.

Bull: I got to meet Danny a long time ago, back in the late 90s, early 2000s. I think it was a - I think it was a special seminar on ethics and principles in broadcast journalism that Ken Mills and Al Stavitsky, Tripp Sommer, had all collaborated on back for what was then called the Public News Directors Incorporated Organization. Now it's Public Media Journalists Association, and I believe Danny Miller was one of those who was brought in as part of this collective think tank to kind of just share best practices, philosophies and things to consider when you're doing public broadcasting. What are some of the best principles and guidelines to go by? So I just remember him talking about his work Fresh Air. And I just thought to myself that is a - at that time, even it was a long-standing relationship. But yeah, you two have been working in tandem with each other supporting this program for almost half a century.

Gross: Yikes! When you put it that way....

Bull: But it speaks very well to the working dynamic and respect I think you two have for each other.

Gross: Oh yes, absolutely.

Bull: Fresh Air became an NPR program in the 80s, quickly gained a national reputation for insightful and probing discussion that went beyond press releases and similar marketing. Was it intimidating at all for you to be part of this expanding network, which had you soon talking to all types of celebrities, politicians, authors and journalists, who, you know, maybe you hadn't before on a national scale?

Gross: It was a lot of pressure, you know, in order to be a national show, to have station managers and program directors wanting to carry the show. So you have to start strong. But it took us a while to really get our footing. In a way, it was fortunate that the Iran-Contra hearings happened early in our beginning as a daily national show. It was heartbreaking at the time because we were working so hard and getting preempted most of the time. However, it gave us a chance to figure out what we're doing and how to do it without a whole lot of people hearing it. So in a way, it was a lucky break.

And another thing I had to learn to do was interview people long distance. I had interviewed people by phone before, because in WBFO, we had what was called at the time, a “tie line” where you could call a certain number of people per month for free. These are the days when long distance calls cost a lot of money and we had no budget so - but you could call with the tie line for free any place in New York State.

So we’d call out to New York City all the time and you know, and other places in New York, and interview people who were sometimes fairly well known, but, but when the show went national and we had access to, you know, celebrity name people, yeah it was, it was, it was intimidating. But on the other hand, a lot of people were saying no because they didn't know who we were yet, so it was hard to get some of the bigger names, but - but we eventually did.

Bull: It seems that everyone with a recorder and microphone can do their own talk show or podcast these days. How do you make, how do you and your team make Fresh Air distinctive from the hundreds of online competitors that have popped up with the advent of the internet and social media?

Gross: Well, it is very competitive out there now, and we do what we've always done, we try to just do like, long form in depth interviews with without a lot of just chit chat, and keep - to keep the interviews like focused, to go as deep as we can without intruding on our guests’ privacy, and also a lot of the podcasts now are very - can I say boutiquey - in the sense that they have a narrow spectrum that they cover. It's all about, you know, one subject - it's just film or it’s just music, or it's just books or it’s just news, and we have a diverse set of subjects that we cover in a diverse set of gas. So if you're looking for one flavor - you're not going to get it on our show, you’re gonna get a bunch of flavors.

You know, right now, I have a co-host, and then other people, a couple of producers from our show, as well as Dave Davies, who's been a part of the show for decades, also do interviews, and they - we each have different things that we specialize in, and you know our passions are similar, but kind of different. So it's, there's a thing, a sense of it being, you know, well, well rounded, but similarly, all the interviews we try to go as deep as we can.

Bull: Can you walk us through – I don’t know if there's a typical day for you or not. I imagine you are a voracious reader and listener. But you know a lot of times as I do, as I'm sure many other people do, think about how you develop ideas for your shows, your guests, working on the questions. What - what um, again - maybe it’s not an actual typical thing. But can you just tell me, what a typical day for Terry Gross and Fresh Air is like?

Gross: Well, on a typical day, if there is a typical day, I come to the station, and I'll start with the night, because the night prepares for the morning. At night, when I come home after dinner, I typically write up my questions, or I finish the research and then write up my questions and write an intro to the next morning show - the next morning's interview, because my interviews are usually at 10 o'clock or two o'clock. If it's at 10 o'clock, I try to come in with everything written. Everything prepared. I do the interview, which is usually somewhere between 90 minutes and an hour and 45 minutes cus’ I’m greedy and I often go overtime. It's supposed to be 90 minutes that I record. And sometimes there’s technical problems that intervene. And then after that I take a walk, have lunch, talk to all the producers and see what they’re up to. They often have things they want to ask me, respond to email, and then I get to work preparing the next interview.

And then there's all kinds of meetings. I'm an executive producer of the show, along with Danny, we're both executive producers, so there's always meetings of all kinds pertaining to every aspect of the show. So that - that eats up a lot of time, but I spend as much of the afternoon as I can preparing for the next interview I'm going to do.

Bull: And when it comes to choosing an interview, are you looking at the headlines? Are you going through an inbox which is probably jammed with press releases and invitations? I was just curious to know how you determine what gets on and what does not get on Fresh Air?

Gross: Well, our producers have different beats. We have Monique right now, who's doing the news interviews, and Lauren and Anne Marie. So it's Monique Nazareth, Lauren Krenzel, Ann Marie Baldwinato, that I'm referring to. So Lauren and Anne Marie do movies and television and other forms of entertainment - you know, music. When I say entertainment, you know, arts, pop culture. And then Sam Briger does the books, and he and Anne Marie also do some interviews on the air.

So each producer goes through everything pertaining to their beat that they think might be possible for an interview, and then they present me with, like the finalists, you know, and then I go through, like the books that Sam has picked out for me to look at, the news stories that Monique thinks I might be interested in, the movies and TV shows or music that Lauren and Anne Marie think I might be interested in. And then we have a very long meeting on Fridays with the whole staff in which we go over all the ideas that are on the table and select the ones that we really want to follow up on.

Bull: That sounds like a really full day.

Gross: Well, we don't have that long meeting every day that's on Fridays.

Bull: Okay, okay.

Gross: But going through all that stuff that's - that's time consuming. Yeah.

Bull: This has probably changed a lot from Fresh Air's earliest days there at WHYY when you first signed on as a host, I would imagine you've got a more streamlined process and a larger staff?

Gross: Well, when the show was local, the staff was me, and until - and then there was a volunteer who had sometimes come in, a couple of volunteers who’d sometimes come in. But when Danny came in 1978 you know, and we became a team, he was an intern. So he wasn't necessarily there every day, but it was suddenly the show. Instead of just being overwhelming, it became more fun. It became more enjoyable. You know, sharing it with somebody. We had very similar interests and tastes, and we were so frequently on the same page about things, it was just so much better. And he lived a couple of blocks away from the radio station. So if it was really snowy and no guests were willing to show up, he would just like run home and bring some records, you know, that we didn't have, you know, in our tiny, little library - music library, because it was a large classical library, but not so much other things.

Bull: So he’d diversify the playlist a little bit.

Gross: Yeah. And then once the show went national, we were able to, like, really, hire a staff. And when it was weekly national, we were able to hire one other person to produce the weekly show. So first we hired that person to produce the weekly show. Then we hired, you know, a sizable staff to produce the daily national show.

Bull: I've worked at a number of stations all across the U.S., many NPR affiliates, and volunteered at a couple seasonal, not seasonal, a few community radio stations. And it almost always seems to be that the local taught her public affairs program is a staff of one, maybe two, if there's a volunteer, and so I imagine that it must be a tremendous relief to have a team that includes Danny and your team of producers to kind of just keep things going, and therefore you're not feeling that overwhelmedness and the ability to take something and make it fun, because that is kind of why a lot of us stay in public broadcasting, especially - is that it's fun, it's enjoyable, but when you're stretched thin and your bandwidth just isn't there, it could be very formidable to try to get a program on every day.

Gross: Yes, it's always fun (laughs) It's very formidable, even with a sizable staff, to get the show on every day. However, it's worth it, like the pleasure of doing the interviews, the pleasure of working with a team of people that I really like, and being able to talk about movies and TV and books and the news with people I really like, who I work with, and with the people creating the things I really like, and investigating, you know, doing the investigative journalism - that's, you know, that's still really exciting.

Bull: Is there a guest that you'd really like to have on Fresh Air, but haven't landed yet?

Gross: Um, I don't know. I mean, most of the people who I've really, really wanted to get have been on the show. Might have taken us a while to get there, but it's more now about finding the people who have just really come into themselves, and you realize that they're really great, because the - you know, they've matured into what they're doing, they have stories to tell. They have, you know, like a number of works, that are worthy of discussion. A - more interesting, more interesting insights into their work as they've been doing it longer. It's a great time to get somebody also before they've been interviewed 100,000 million times, and I want to talk to them anyways, even if they have been.

But I think it's harder for people who have been interviewed a whole lot, because they feel like “I've told this story 100,000 times, and anyone who cares about me has heard it already,” so it kind of pains them to tell it again, even though not everybody has heard it.

And in order to get to places that people haven't heard - you have to kind of build up, I don't mean puff up. I mean just kind of build some groundwork for who the person is, because not everybody knows who everybody is, even if they're famous. Because especially nowadays, people are famous in certain parts of the esthetic world. You know, there's so many different TV shows and so many different movies and so many different books and recordings and Spotify and iTunes and all of that. So the audience is really fragmented. I mean, you know, audiences for works that we all used to have in common that doesn't quite exist to the same extent it used to. Audiences are fragmented, and they don't know necessarily what the other fragments like, you know what I'm saying.

Bull: I know what you're saying. And it seems like a lot of that fragmentation has come with the advent of social media and the internet, which I recall is just being a dial up device back in the late 90s in people's homes. But, you know, we saw websites and blogs and then vlogs and podcasts, and it seems that the–

Gross: And streaming, there's so many choices. You can there's like, it's overwhelming when you want to, like, choose something to watch. There's like, too many choices. It can be paralyzing unless you know what you want to see.

Bull: The variety can be crushing at times. And I also wonder too, that if that affects maybe the media landscape, and that people who used to really, really need to be on a program like Fresh Air or the CBS Evening News or the Today Show, maybe don't feel that that's a, you know, the make or break option anymore. They can do their own podcast, or get on Joe Rogan or someone else who has something out there. I mean, it just seems like the offerings are endless. But I don't know. I still think that when you have a program with the name recognition and prestige that Fresh Air does that - you know, going back to my original question, maybe it's, it's not so hard to land those guests now, because they recognize the value.

Gross: Well, we do get a good deal of the guests that we want, and we're very lucky in that respect. And also, we're a part podcast as well as a broadcast, so it has a pretty far reach. As you know, it's not like Joe Rogan range, but you know, for the world that we operate in, you know, for the kind of show that we do, I'd say we have a, you know, reasonably broad reach.

Bull: As there a moment in your career, Terry, that you were especially proud to be working in public radio?

Gross: I'm always proud to be working on public radio. I mean really. So I don't know who to single out in particular.

Bull: No particular guest or topic that you tackled, that you feel that you, you and your team really did well on?

Gross: Well, of course there are. But the thing is, like, if you're if you have a daily show and you have a network that's a daily 24-hour network, on a station that's a daily 24-hour station, it's - a lot of it is about the accumulation, the constancy and consistency of what is, you know, what is podcast or broadcast, rather than, like this highly polished thing that stands out, or there's like one moment that stands out.

Bull: Sure, no, I mean, I think it's got a spectacular record of great talk and conversation, insightful analysis of politics certainly makes up for those more difficult guests. I mean, I still remember Bill O'Reilly and Gene Simmons and a handful of others who were very confrontative and very defensive and at the same time, you know, I think it showed your talents as an interviewer too, that people may have tried to placate them or caved in. But it seems like there is always kind of a standard bearer to be had in conversations that you could remain -- you can disagree about certain points and not turn it into some kind of fiery confrontation on-air. But I thought, you know when I think back to those moments and how he handled them, I thought you did an impressive job and still hold out as a great example of how to handle difficult people.

Gross: Yes, and Bill O'Reilly walked out. So there wasn't…he was confrontational, but he didn't give me a chance to answer back, so I kind of answered back after he was gone. I said, “So I guess that's the end of this conversation. He's walked out, my guest has been Bill O'Reilly.” So, I didn't like confront him, I didn't insult him, but we played the interview, we played that speech that he made at me, accusing me of throwing every - basically accused me of insulting him and throwing of defamation. That's what he accused me of, defamation. Anyhow, it was - it really paid off that interview. And Gene Simmons as well, because I played the most confrontational on their part - excerpts during many, many speeches that I've given, when I illustrate my points with excerpts of interviews, and I have to say, they always get laughs.

Bull: So we're winding down here. I know that you are on a schedule, obviously, Terry, do you have any final thoughts or comments to share, either about your career or the state of the public radio industry today?

Gross: About my career, I just say I feel very lucky to have had one. And about the state of the industry, I'd say, “Wow, I wish I knew. I wish I could see into the future.” The whole media landscape now is a very confusing place to be. Funding models are changing. Listeners and viewers are moving to places that didn't used to exist, and that's affecting the funding models for newspapers, for broadcasting, for cable, even for streaming.

Because, you know, Netflix used to basically own streaming. Like they were the streamers, and now, every TV network and all kinds of other channels, streams and whatever you're looking for, still, you won't necessarily find it (laughs), you know, in terms of the television part. I mean, I guess you will, if you had all the streaming services, I guess you will, but it's going to be confusing trying to, you know, make choices sometimes, but, but anyways, no one, no one can predict the future right now.

And everybody, everybody, even the streaming services, are struggling in their own way, because the streaming services have so much competition that they didn't have when it was just the Netflix era. And that, you know, HBO was in a great position when it was just like the HBO era. And now they have some, they have other networks who are doing similar things that they're competing with.

Bull: Very true, very true.

Gross: And public radio is probably about to be -as we record this at the end of 2024- it's probably about to be threatened. Some of its funding - threatened by the Trump Administration, which makes it even harder to predict the future.

The people who will suffer most from that are the small radio stations that can't afford to pay fees to NPR, because it's a fee-based member station kind of network. And if you take away federal funding from some of the smaller stations, who knows what will happen, but they might not be able to continue to be NPR stations. And that will hurt people in small towns, on reservations, which they sometimes have public stations, you know, places that aren't big cities.

Bull: Places where maybe education is lacking, where people just don't have a lot of exposure to outside communities and perspectives different from their own. Yeah, it's - it's going to be a very uncertain time in the coming administration, and I know that it's been repeated time and time again. Certain politicians want to defund NPR, but it will be very, very daunting to see what comes in the next few years for the public radio industry.

And I hope that Fresh Air continues regardless. But that asked or that put out there, Terry, you - last question for me is- how much longer do you expect to be hosting Fresh Air?

Gross: If I knew the answer, I would tell you (laughs).

Bull: Fair enough. (laughs) And this concludes my interview of Terry Gross, December 27, 2024. Terry, thank you so much for making the time to talk to me about your history and contributions to NPR. Fresh Air remains a great example of insightful and in-depth conversation, and remains an NPR favorite by millions of listeners and colleagues. So it's been an honor to have this conversation, and I wish you and your crew well in the new year.

Bull: Thank you, Brian, and thank you for talking with me, and thank you for doing this oral history project.

Bull: It's been my pleasure. Thank you again.

===================================================

The Public Radio Oral History Project was started by Ken Mills in 2022, as a way to preserve the accounts of the American public radio system's earliest pioneers, innovators, and personalities. It's currently headed by longtime radio journalist Brian Bull, a former NPR editorial/production assistant for Morning Edition, and participant in the NPR Diversity Initiative.

Copyright 2024, 2025, KLCC.