Decades after he carried out the Thurston High School shooting, convicted murderer Kip Kinkel has broken his silence.

Today, HuffPost has published its article, Kip Kinkel Is Ready To Speak, by reporter Jessica Schulberg.

It’s based on 20 hours’ worth of interviews conducted over a 10-month period, starting last summer. In the piece, the 38-year-old Kinkel gives several new insights into his mental state before and after the incident, as well as his transition to life behind bars.

But HuffPost’s audience will be particularly intrigued to read Kinkel’s reflections on how his case has influenced juvenile justice reform efforts across Oregon, which are fresh and follow legislative wrangling inside the statehouse in recent years.

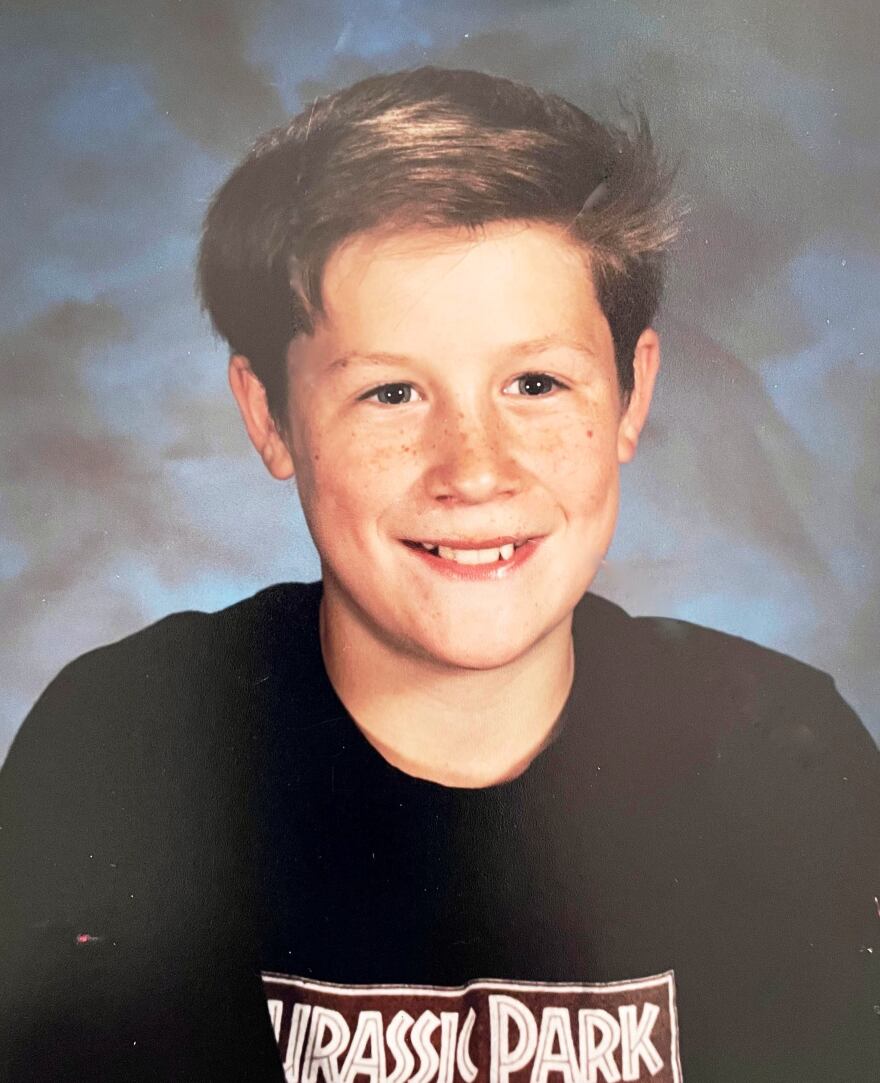

Across Springfield and Eugene especially, the Thurston School Shooting is still a raw wound on the community’s collective memory. Over a two-day period in May 1998, then 15-year-old Kinkel fatally shot his parents, two classmates, and wounded 25 others before being subdued in the school cafeteria.

At the time, it was deemed one of the worst mass shootings at a public school, and preceded the Columbine Shooting in Colorado by roughly a year.

Immediate testimony and interviews showed Kinkel to have experienced delusions, episodes, and auditory hallucinations consistent with paranoid schizophrenia. He heard three distinctive voices, alternately denigrating him and compelling him to “kill everyone in the world.” He also believed that the Walt Disney Corporation had implanted a chip in his brain, and government gun-control efforts would inevitably leave the U.S. defenseless against an imminent Chinese invasion.

As reporter Schulberg points out in her article, Oregon voters approved Measure 11 in 1994, roughly four years ahead of the Thurston violence. The measure mandated minimum prison sentencing requirements for specific crimes, as well as requiring juveniles 15 years-old and older to be tried as adults for certain offenses. This meant Kinkel could receive several hundred years in prison if convicted. Prosecutors offered a plea deal that would lead to a sentence of 25 to 200 years, depending on the judge’s discretion with the 26 attempted murder charges against the youth.

Meanwhile, Schulberg adds, Kinkel had been off his psychiatric medications for several weeks, and was experiencing the voices again. The youth had not yet accepted his diagnosis and was terrified of being deemed “retarded.” Neither a mental institution nor prison appealed to him, and his anxiety over even brief courtroom appearances felt unbearable. Pressure from the Springfield community to reach a quick resolution was also evident, and days ahead of the trial, Kinkel was found curled up, hearing voices, and suffering a panic attack.

Kinkels’ legal team was expected to use the insanity defense at his trial. But in September 1998, he instead pleaded guilty to killing his parents, Bill and Faith Kinkel, at their home on the night of May 20th, then entering the Thurston High School cafeteria the next day, peppering the space with 50 rounds fired from a semiautomatic rifle. 16 year-old Ben Walker and 17 year-old Mikael Nickolauson died from their wounds. Altogether, Kinkel was charged with with four counts of aggravated murder and 26 counts of aggravated attempted murder (one from an assault against a Springfeld police detective in an interview room.)

Kinkel was sentenced to 112 years without parole, which to many in the grieving community, provided a sense of closure and justice. But Schulberg’s article notes that while Kinkel had signed the agreement to plead guilty days earlier, he hadn’t had the chance to read most of the document. And there’s question as to how mentally able the youth was to comprehend his legal options.

Today, Kinkel is one of nearly 10,000 people in the U.S. serving life for crimes committed while juveniles. Justice advocates argue with their brains still developing, many young people aren’t capable of exercising restraint or grasping the repercussions of their actions.

Schulberg adds that more than 20 years since the Thurston shooting, Kinkel remains one of the most infamous examples used whenever juvenile sentencing is debated. She writes about Oregon’s SB 1008 – introduced in 2019 –where prosecutors and hardline “do the crime, do the time” pundits inaccurately framed the bill as one that would instantly release Kinkel from prison (its original language ended life sentences without parole for minors, and created early-release opportunities for those showing rehabilitative progress.)

Even after it narrowly passed, Schulberg writes that hyped-up fears over a free-roaming Kinkel prompted lawmakers to amend SB 1008, to exclude those sentenced before its passage. That event ensured the likelihood Kinkel will spend his life entirely behind bars, “but it also affects hundreds of other people in Oregon who are in prison for crimes they committed as kids — including people who have played a role in Kinkel’s rehabilitation.”

On that note of rehabilitation, Kinkel’s sentencing did provide actual care for his mental illness. At the MacLaren Youth Correctional Facility, he was provided intensive group therapy, and medications that diminished the voices and delusions. The article explains that eventually, Kinkel realized that the Disney brain chip and impending Chinese invasion weren’t real. He even renewed his academic studies, earning a college degree in global studies before aging out of MacLaren in 2007.

And yet, Kinkel tells HuffPost that there was still pain resonating from his actions in May 1998.

“There was a sense of, ‘I did these things. I hurt these people. I killed my own parents, who I absolutely loved and who loved me and were good people. I shot and wounded completely innocent people that didn’t deserve anything bad to happen to them at all. I killed two boys who were completely innocent. And I need — I have to understand why I did this,’” Kinkel said.

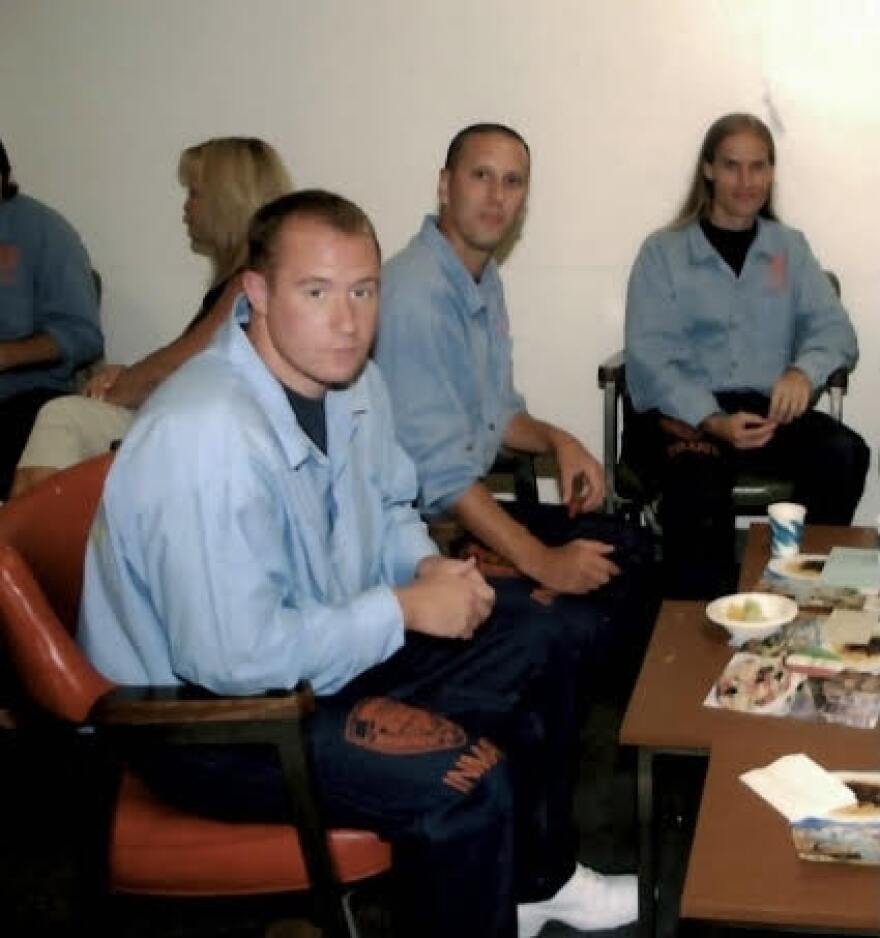

The Huffpost article also shares more about Kinkel’s transition to Oregon State Correctional Institution, and how arrangements were made to make it as smooth as possible given his notoriety. Prison gang members anxious to score points sought to start fights with him, seeing Kinkel as a high-profile target. But reporter Schulberg says two inmates were recruited by Kinkel’s psychologist at MacLaren, to work with the gangs and discourage making the new arrival as a target. Outside of one early scuffle that got Kinkel placed into solitary confinement, the transition largely went okay.

Schulberg’s article says since then, Kinkel pays it forward to other young men coming into OSCI. Kinkel and others give the new arrivals items like toiletries and commodities, as well as guidance to help adapt to prison life and avoid violence.

“We try to welcome them into a community,” Kinkel told HuffPost. “We look at it as a community of guys who are basically trying to do the right thing and just survive this environment.”

As previously reported by KLCC and affirmed in the HuffPost article, Kinkel now works as an electrician at OSCI. A former cellmate says he and Kinkel bonded over reading works like James Joyce’s Ulysses and Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment. And Kinkel has also become a certified yoga instructor and according to his childhood friend, Tony McCown, has an “odd, centered peace” to him.

At the same time, Kinkel tells the HuffPost that he’s struggled with how he doesn’t want his past actions to be used to restrict the opportunities for other lifetime inmates who committed crimes in their youth. This struggle compelled him to finally speak, after more than 20 years of shunning countless invitations by the media.

“I’ve never done this. I’ve never done an interview,” Kinkel told Schulberg. “Partly because I feel tremendous, tremendous shame and guilt for what I did. And there’s an element of society that glorifies violence, and I hate the violence that I’m guilty of. I’ve never wanted to do anything that’s going to bring more attention.”

“I have responsibility for the harm that I caused when I was 15. But I also have responsibility for the harm that I am causing now as I’m 38 because of what I did at 15,” he said.

Kinkel’s prospects for release were not only stifled by SB 1008’s amendment, but more recently by the U.S. Supreme Court. Its new conservative majority – after years of demonstrating increased leniency for juvenile offenders – did an about face in April, ruling by a 6-3 vote that a judge doesn’t need to make a finding of "permanent incorrigibility" before imposing a sentence of life without parole.

“It was a mean-spirited decision,” Kinkel told Schulberg shortly afterwards. “It’s soul crushing. I don’t know how else to describe it. Those justices … basically just told us to go die. That our lives don’t matter. That our existences don’t have any meaning. That our future should only be torment, pain, suffering and misery.”

The debate over the sentencing of juvenile offenders will continue to see justice advocates -who argue youth don’t think or behave in ways comparable to adults – pitted against judicial officials who take a brass tacks, punitive stance against severe criminal acts, regardless of age. And while Kip Kinkel’s prospects of having his sentence commuted are murky, the one clear reality appears to be that his name will be thrown into the debate for years to come.

You can find the HuffPost article Kip Kinkel Is Ready To Speak here.

Copyright 2021, KLCC.