A museum exhibit in Springfield is celebrating Hispanic Heritage Month by featuring traditional Charro and Charra attire. The museum is also recognizing a long lost South American relationship. KLCC’s Melorie Begay toured the exhibit with a few of the organizers.

Walk into the Springfield Museum and the first thing you’ll probably notice is the rugged smell of leather. It’s enough to draw your attention to a large brown and white saddle fitted wit layers of leather straps, silver, and rope. Antonio Huerta says the exhibit is meant to showcase the craftsmanship of the Charro tradition.

“The saddle all of the equipment has a very high influence from Spain. The sport itself was sort originated as part of the work that our Mexican indigenous ancestors did in the Hacienda, or the fields in Mexico,” says Huerta.

Huerta owns the saddle and all the Charro outfits on display and is himself a Charro.

“I love this saddle I have owned it for maybe five or six years and to me it looks just as good as when I bought it,” he says.

Huerta and Eugene ArteLatino’s Jessica Zapata, helped source a few of the pieces in the exhibit from people in the community.

Zapata points to two dresses from Jalisco and Nayarit, both of which were loaned by a Folklórico dance teacher. The top half of the Jalisco dress is bright pink and lined with white lace, with a blue flower patterned skirt.

“So you will see in Mexico is each state has the main dress but also the small towns have other traditional dresses, and this is mainly from Jalisco to dance El Jarabe Tapatio,”she says.

The outfits highlight the diversity of Mexican culture as shown by patterns, colors, and layers, says Huerta. He points to dresses from Chiapas.

“If you look at these dresses they’re kind of one piece you know. They’re not as wide as the Jalisco, or Nayarit because they don’t wave the dress as much,” says Huerta.

The dresses aren’t just region specific they’re also music specific, says Zapata.

“So if they dance another song, they have to wear different dress. So you will see the presenters, the dancers, they will change every song,” Zapata says.

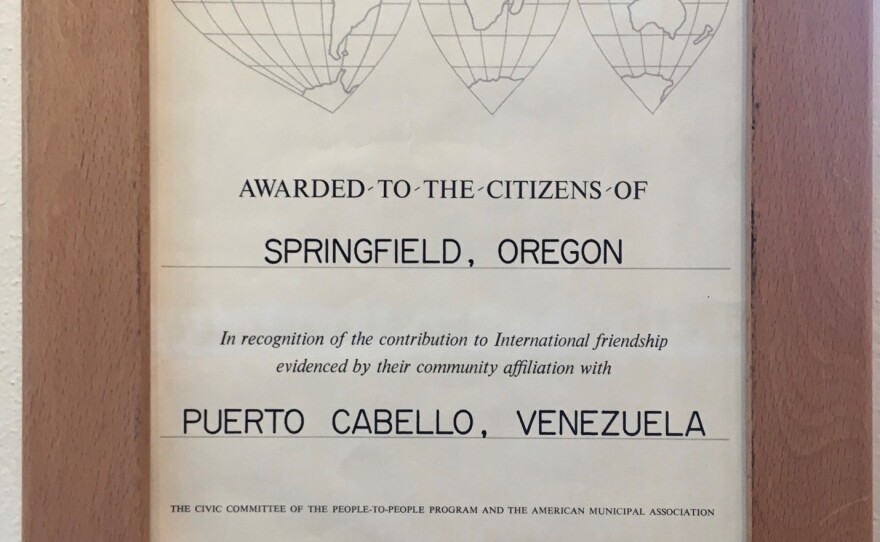

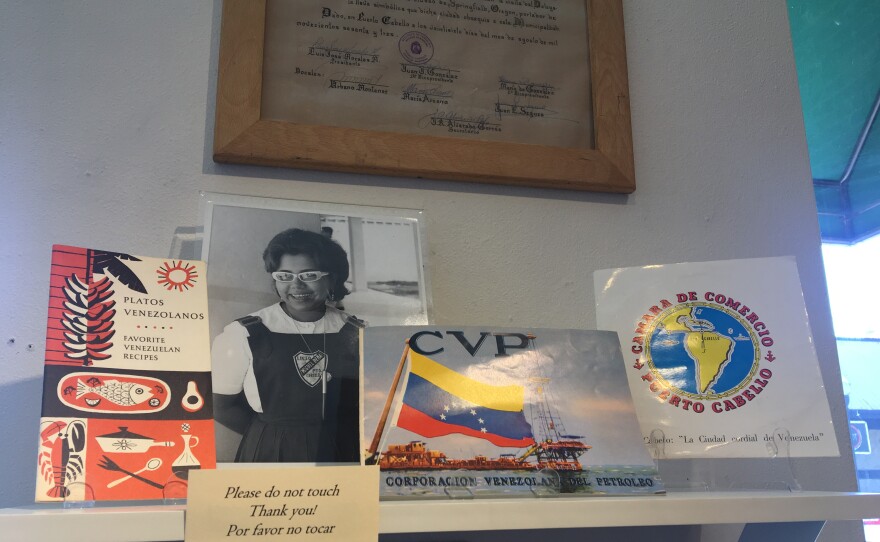

The exhibit also features photos and documents from the early 1960’s revealing a sister city relationship between Springfield and Puerto Cabello, Venezuela. Springfield Museum Curator Madeline McGraw says she and the Springfield librarian made the discovery by looking through old boxes.

“We don’t know when that relationship ended but we do have a lot of artifacts relating to the beginnings of that program. And travel between Springfield and Venezuela, and you know materials that were brought back and materials that were shared and so we wanted to at least put a small amount of it on display,” McGraw says.

“We don’t know when that relationship ended but we do have a lot of artifacts relating to the beginnings of that program. And travel between Springfield and Venezuela, and you know materials that were brought back and materials that were shared and so we wanted to at least put a small amount of it on display,” McGraw says.

Although Lantinx culture may not have originated in a city known for logging, pioneers, and a forgotten sister city, it’s significant to Springfield’s increasingly diverse population.

“I think now a days with the current climate around immigration, immigrants, or communities of color in general, it is important to share things that we have in common and art, culture, traditions, are all a part of us,” Huerta says.

This act of voluntary cultural exchange is what the exhibit aims to do. Curator Madeline McGraw says museums have often ignored marginalized communities. But this is Springfield’s attempt to move away from singular narratives, and instead create a more inclusive space.

The exhibit will host a special event during the Springfield Second Friday Art Walk on October 11. The last day to see the exhibit is October 26.