When it comes to near-shore earthquakes and tsunamis, Oregon’s coastal communities have moved beyond awareness and are taking action. As part of our series on Oregon's Natural Resources and Resilence and funded by the UO Wayne Morse Center for Law and Politics, we find there are some controversies and complications.

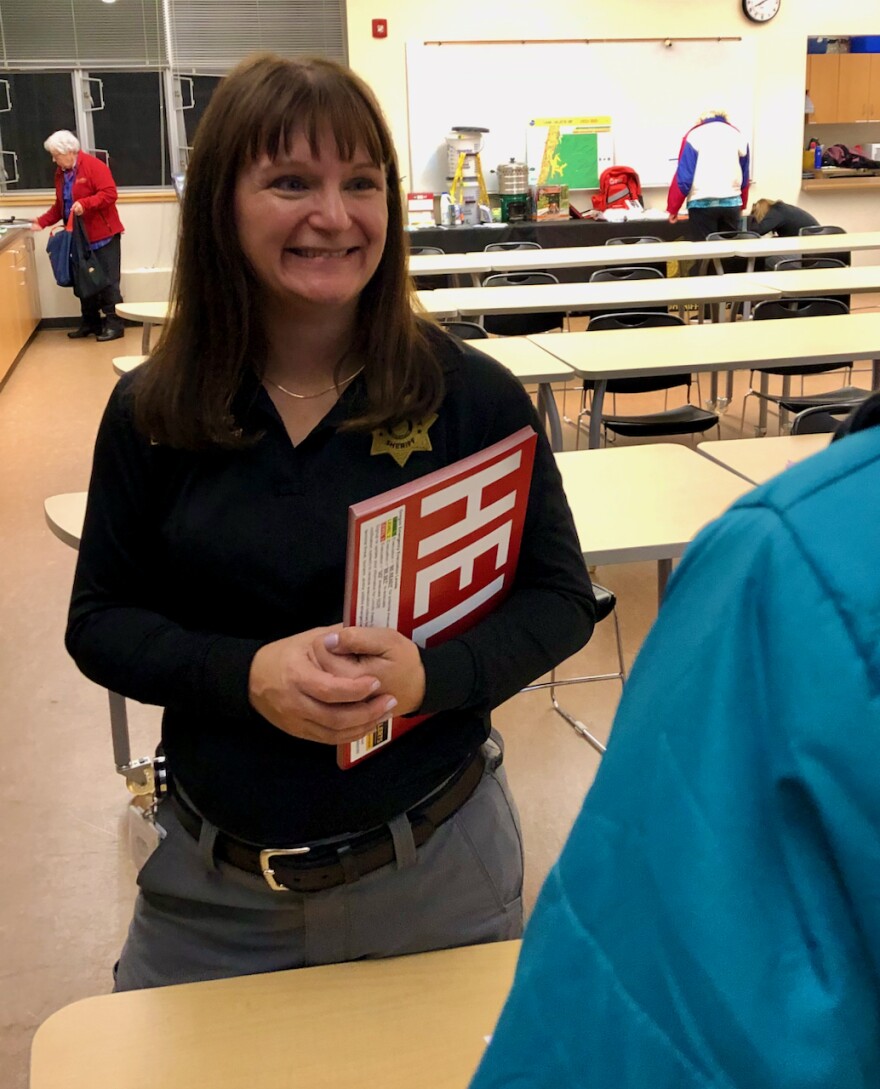

Lincoln County’s Emergency Manager Jenny Demaris has given dozens of Cascadia earthquake presentations. She’s energetic and engaging, and holds nothing back in sharing details of the destruction a 9.0 subduction earthquake would bring:

Demaris: “You have to be more than prepared, you have to be a resilient person. Things are going to be stretched thin. It’s gonna be rough.”

Meagher: “We attended a Cascadia preparation event in Yachats, where Jenny scared the pants off everybody, and that’s what got me started, frankly.”

Michael Meagher lives north of Waldport. Since that first meeting, he’s made “go kits” for his house and car and gotten his ham radio license. He’s now part of the state’s “Two Weeks Ready” development team. That kind of engagement is exactly what Demaris wants:

Demaris: “The eventual goal is to change the cultural mindset of the people that live and work in Lincoln County and the people that come here to vacation. I absolutely need them to understand that there is a responsibility that is on their part.”

She emphasizes not only the awareness needed to get moving the moment the ground shakes, but also the many months of self reliance necessary until public roads, water, sanitation and communication services are restored.

Althea Rizzo is the earthquake expert at the Oregon Office of Emergency Management. She says the science on Cascadia-level events is broadly accepted.

Rizzo: “More funding is becoming available as people have acknowledged that this is a real hazard that needs to be addressed. It just comes down to the community itself deciding that this is a priority.”

Voters in Seaside passed a bond in 2016 to move all their schools out of the tsunami zone, and the new campus opens next fall. Lincoln City’s new hospital, built to operate for two weeks without public water or electricity, opens February 2020, and several communities including Yachats have moved essential services to higher elevation.

Rizzo says a new state program will likely bring even more infrastructure changes. It’s a set of precise coastal maps called “Beat the Wave.”

Rizzo: “It shows people how long it takes to get to high ground at various speeds, like does a slow walk get you to safety in time, does a fast run get you to safety in time? So it starts to show us where we might need to put vertical evacuation structures.”

Vertical structures might be existing tall buildings, reinforced for disasters, or new stand-alone towers.

The OSU Marine Studies Building is a vertical evacuation facility under construction in Newport’s South Beach. The $60 million building will house research labs and promote collaborative studies. A wide ramp allows access for 900 people to wait out a storm on the roof. It’s only the second such building in the country. Facilities Research Coordinator Cinamon Moffett says the project was a learning process for the construction company. There were many things no one in the U.S. had done before:

Moffett: “We do a lot of tours already, even before the building is open, for folks that are interested in different aspects of the technology.”

Chris Goldfinger is a Geology professor at OSU. He says almost the entire earth science department objected to building on a sandbar in Yaquina Bay. The site didn’t move, but the engineering changed:

Goldfinger: “OSU gradually updated the plan until now it’s a fortress, essentially. It can withstand hits from ships floating loose in a tsunami. However, it’s sort of an attractive nuisance in the sense that it created a hazard that didn’t previously exist.”

Goldfinger says it puts more people in harm's way who might rush to the building to get up the ramp. OSU got a special permit for the structure. Had it waited a few years, permitting might have been easier. At the end of the Oregon’s tumultuous 2019 legislative session, lawmakers repealed a ban on building new critical structures, such as fire stations, in tsunami zones.

Rizzo: “Previously we had a line in law that was developed in 1995 by George Priest using the best available science of the time. Recent legislative action repealed that line, but did not give a replacement land use line.”

Soon after the repeal, the cities of Florence, North Bend, and Reedsport changed their land-use planning rules to incorporate tsunami hazard zones. Many others followed. Althea Rizzo thinks the state will end up in a stronger position:

Rizzo: “What we’re seeing is local communities are taking it on themselves to adopt land use regulatory lines, so the state doesn’t necessarily need to have that line.”

Goldfinger disagrees:

Goldfinger: “The problem with having a town by town solution is it’s a little bit Darwinian. It means the towns that have more resources are going to fare better in a tsunami, and that really, almost puts a class structure on tsunami preparedness.”

He says not just having a state rule, but having a consistent Pacific Northwest policy is the best way forward. He’s encouraged by increased public awareness, and thinks funding will follow. But he says politicians, engineers and scientists need to work together to create rules that will best work for coastal communities.

Funding for KLCC’s Resilience and Oregon’s Natural Resources series comes from the University of Oregon’s Wayne Morse Center for Law and Politics.