An Oregon State University professor’s recent op-ed in the Washington Post draws uncanny parallels between the 1918 flu pandemic and the one we’re struggling through today.

Mark Twain once said, “History doesn’t repeat itself. It rhymes.” OHA Humanities professor Christopher McKnight Nichols said when it comes to how Americans deal with a deadly virus, Twain’s sentiment rings true.

From treatment strategies, or the lack of them—to masking to how a virus is weaponized with language (think “Spanish flu” and “China flu,”) Nichols said we’re dealing with a pandemic a lot like our ancestors did 100 years ago.

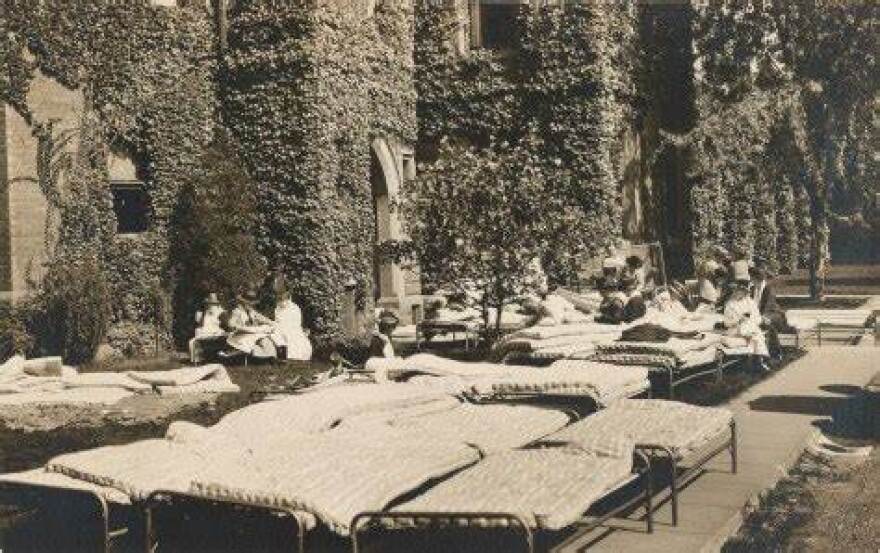

“Things like closure policies, you know Broadway goes dark for a while, schools are closed for a while, they had limits on the number of people who could go into places or could travel on street cars,” he said. “They used a strategy that they called ‘ventilation’ which is leaving windows open.”

Nichols noted another parallel: cities that heeded more cautious public health measures--like masking and closures-- had far better outcomes- and less loss of life- than places that resisted.

Nichols said while it wasn’t overtly political, there was pushback against public health mandates then too. San Francisco even had an Anti-mask League. He added, in 1918 police were used to ensure compliance of mask and closure orders. “Behaviors had to change,” he said.

The cities and states that did the best in the 1918 pandemic where those that put on proactive restrictions early, often before major outbreaks. Cities like St. Louis ordered closure policies in places like schools and churches.

“In 1918, a lot of church leaders really embraced this. They said, ‘for the community public health, we’re going to close churches.’ And one of the ways they did that was they actually sent their sermons out by mail. They tried to be inventive and creative. That was their version of ZOOM.”

Nichols likens the second wave of flu infections in late 1918 to the havoc the Omicron variant of COVID-19 is wreaking today. A pandemic can only end once the virus is seriously diminished. That requires a participative society.

“The big takeaway is that fatigue and resistance to mitigation methods made things worse,” said Nichols. When fighting the H1N1 Influenza pandemic a century ago, “public officials needed to safeguard the public good, even if that meant unpopular moves.”

Another important takeaway for Nichols is that honest, open communication is really important. “In 1918, the Wilson administration didn’t communicate very openly and the flu pandemic was clearly worse. And we saw something similar with the Trump administration. The first instinct of a lot of administrations, maybe regardless of their politics, is to minimize. And that doesn’t work out well for populations,” he said.

Nichols made a contrasting, historical point. Public Health was rather rudimentary in 1918-19 compared to today. There was a Surgeon General and a U.S. Public Health Office but they had no ability to order states to do anything. They issued mostly pamphlets and bulletins that were guidance for local public health officials.

“There wasn’t a uniform, universal approach to public health in the U.S.,” Nichols said. “Other nations actually learned from the pandemic of 1918-19 better than the U.S. For instance, in 1919 Canada formed a federal public health office that had some of those powers but the U.S. did not.”

Nichols said an important lesson that we as a nation haven’t learned yet is to take responsibility for global pandemic preparedness. In the end, we should not forget what we’ve already learned.

Read the Washington Post op-ed by Christopher McKnight Nichols titled

"1918 flu is even more relevant in 2022 thanks to omicron"

https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2022/01/03/1918-flu-is-even-more-relevant-2022-thanks-omicron/