On a street in Rochester, N.Y., earlier this month, police and demonstrators clashed violently, with marchers shouting and coughing as officers in riot gear fired pepper balls at the crowd.

As tear gas fogged the intersection, a Black protest leader urged white demonstrators forward.

"If you're a white person, you're getting to the perimeter, you're putting your body on the f****** line right now!" she shouted to a group of protesters wearing goggles, filter masks and bicycle helmets.

They responded by hustling forward, forming a line with homemade shields.

This dynamic is playing out on streets across the U.S. Protests are massive and diverse, with more Americans embracing the Black Lives Matter movement. But in many cities, the leadership is overwhelmingly Black.

"It's our turn to lead our own fight, to frame our own conversations," said Benjamin O'Keefe, a Black political organizer in Brooklyn where protests have continued since late May after George Floyd, a Black man, was killed while in police custody in Minneapolis.

O'Keefe, who also worked on Sen. Elizabeth Warren's presidential campaign, said it's a hopeful sign for Black leaders that so many white people are turning out for marches.

But it has also meant a complicated conversation with white activists who often haven't grappled with their own attitudes about race.

"We exist in a white supremacy culture in which even people who want to do good do not necessarily want to be led by a Black person," the 26-year-old said.

This conversation among activists is happening at a moment when some Black leaders are pushing ideas about criminal justice reform that once seemed far outside the political mainstream, such as defunding police and abolishing prisons.

O'Keefe said many Black leaders are uncertain whether white supporters are committed to that kind of systemic change.

"Are you really in this? Do you really understand the stakes?" he asks. "Are you here for an Instagram picture? Or are you here because you understand when I walk out the door every day, I have a much higher chance of not returning home because of the color of my skin?"

One street movement fueled by very different lives

A study from Harvard shows that Black Americans are roughly three times more likely to be killed during an encounter with police compared with white people. Black adults are also five times more likely to say they've been unfairly stopped by police because of their race, according to the Pew Research Center.

Black activists say white demonstrators haven't shared this experience, so they often turn up at protests with different assumptions about about what reform should look like and what tactics should be used in the streets.

"White people often come to these protests and they want to lead them and they want to be screaming the loudest and they want to throw things at police," O'Keefe said.

Across the country, many Black organizers are working to address this tension head-on.

"White folks, allies, accomplices, I'm talking to you all," Christopher Coles, an activist and poet in Rochester, said to a crowd of marchers in early September through a bullhorn.

"This is not a video game. For some of you all that come here, you come because it's an elective. We come because it's survival."

Just one block from where the 39-year-old Coles spoke, a mentally ill Black man was arrested and held down by police last March with a spit hood over his head.

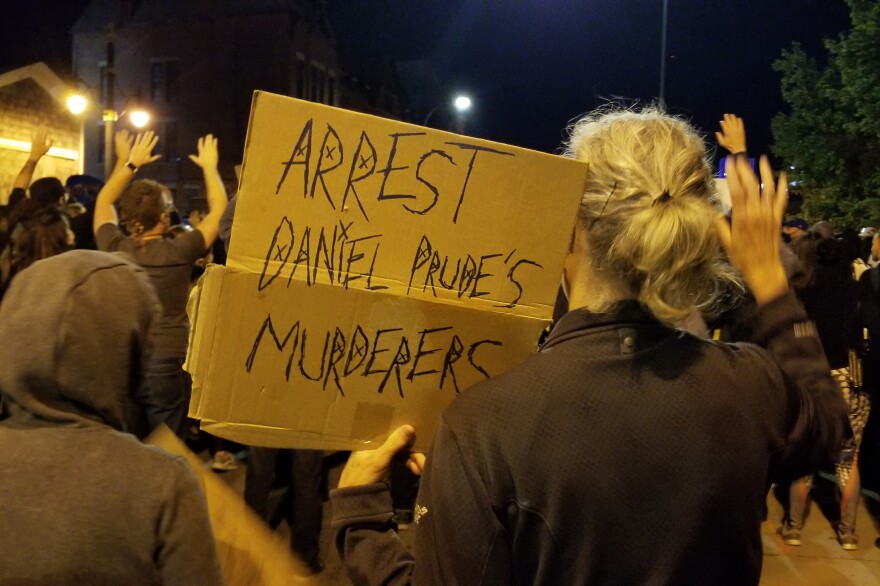

Daniel Prude asphyxiated and later died. Disturbing video of his arrest was released in August, sparking weeks of demonstrations.

Addressing a crowd made up in large part of young white activists, many marching for the first time, Coles voiced a concern shared by many Black leaders. They worry white allies will march and carry signs but then go back to their lives, even if nothing changes to make Black people safer.

"You get to be an ally one day and just white the next. You get to live and lean on your privilege. But if you've got privilege, start motherf****** spending it," Coles said.

Progress on civil rights has long depended on Black leadership

This tension isn't new. During the civil rights era of the 1960s, Black leaders were often leery of white supporters, questioning their commitment and their willingness to be led.

"We were concerned they would assume responsibilities for things we wanted young Black people to assume," recalled Charlie Cobb, who was an organizer with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in Mississippi during the 1960s.

Cobb said he worried when white college students began arriving on buses from the North in 1964.

"Such a large number of whites coming down, I thought they'd overwhelm the still fragile roots of the grassroots movement we were trying to build."

He believes Black leaders back then did find ways to organize and lead white activists, forming an alliance that won significant gains on civil rights. He thinks that's possible again now, as white people take to the streets in much larger numbers.

"I think the leadership should be Black but I don't think that excludes the participation of whites or even search for white allies, as we did with respective to the 1964 Mississippi summer project," Cobb said.

For white allies, listening and "standing alongside"

White activists interviewed by NPR said they're broadly comfortable with this power structure within the Black Lives Matter movement.

Back in Rochester, Kendall Devour was one of thousands of young white people across the U.S. who marched this summer for the first time.

"I just think being a white ally means listening a lot and sometimes that means you're going to make mistakes," said Devour, a graduate student at Rochester Institute of Technology. "But you can't get sad and cry about it; you just have to register that there's work to be done."

Brae Adams, a white pastor in Rochester, volunteered this summer for a Black-organized group that offers counseling and pastoral care to protesters.

"We're just standing alongside, we are allies only," she said. "We don't claim any of this as our own. All we're trying to do is be a support and stand and say, 'Yes, indeed your life does matter.' "

Some cities and state legislatures have responded to these protests with modest police reforms. But Black organizers and many of their white supporters say it's not enough.

They plan to keep marching and demonstrating together, demanding change as long as Black people keep dying in police custody.

This means this conversation about race will also continue within the movement. It's playing out mostly among young people, Black and white, at a time of huge stress as they're exhausted after weeks of confrontation with police.

But Salomé Chimuku, a 29-year-old organizer in Portland, Ore., says the relationship between Black leaders and white allies is mostly working. She's seen friendships forming in the streets that wouldn't have existed without the protest movement.

"Whether or not it's always pretty, having these conversations is moving things forward," Chimuku said. "I think it's going well, the fact that we're still talking about it, the fact that these protest are still going on past 100 days shows that it's successful."

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.