The city of Eugene says it has fewer per capita staff now than it did before the Great Recession - and it's about to make more cuts.

Officials say high inflation and staffing costs - paired with slow property tax growth - are to blame.

During last year’s budget deficit, Eugene made cuts to the library budget. This year, it's in the midst of a city-wide hiring “pause.”

Chief Financial Officer Twylla Miller said the city’s also looking for savings in its health plan, is trying to sell off surplus property and considering several fees.

While those changes will address this year's deficit, Miller said the same escalating costs are likely to be a problem again.

"There are a lot of factors that cause expenditures to grow faster than revenues," she said. "Many of those things are beyond our control, such as continued PERS rate increases, high inflation. And of then, of course, we have an expanding community. We have increased service demands as we look to the future."

City Manager Sarah Medary said the challenges Eugene is facing are structural: The bulk of its funding comes from property taxes which have been capped by state law for decades. At the same time, Eugene has grown dramatically, along with inflation and staffing costs.

Medary said the city is spending less per resident now than it did in 2008, and has 1.6 fewer employees per capita than it did in the 90s.

"It's almost the same as if the city manager said 'Hey, we're going to take over all of Springfield,'” she said. “We're going to take over their governance, we're going to do their IT, their HR, we're going to maintain their parks and their streets, all of those things that are general funded without any additional staffing. That's essentially what's happened. We've taken in a whole new city over the last 28 years and we have less people."

Lindsay Tenes, a lobbyist with the League of Oregon Cities, said many local governments across the state are facing deficits. Most have been struggling to balance their budgets since the passage of two ballot measures in the 1990s constrained tax rates and taxable property values.

"They get the amount of money that they get and then they have to figure out how to fit all the services within that budget," she said.

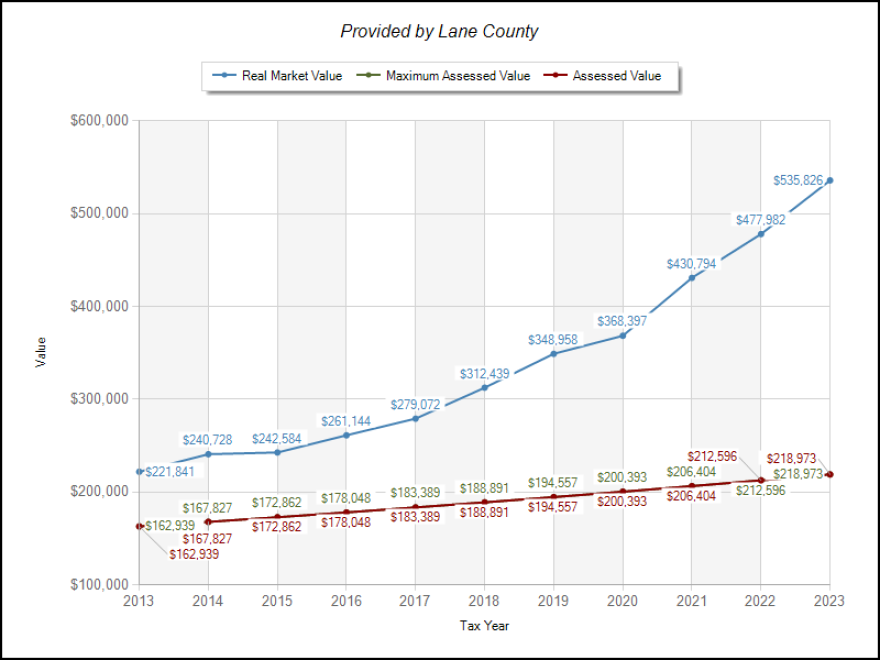

Measures 50 severed the taxable, or assessed value of a property from its real market value. In practice - the law only allows taxable value to increase by 3% a year from what a property was estimated to be worth in the nineties. In contrast, real market values have fluctuated wildly, flattening during the great recession and increasing by double digits in the last few years.

According to the Lane County Assessor’s office, the median assessed value for a single family home in Eugene is roughly $246,000. The average real market value is around $487,000.

Tenes said that widening gap has meant that Oregon cities experiencing rapid growth, gentrification, and cost of living issues are also often facing budget deficits.

“Property values have changed so much since then,” she said. “There’s really no way for cities to capture the true cost of providing services to new residents with new growth.”

A check on spending?

But not everyone sees a downside to limiting property tax increases. Jason Williams is the co-founder of the Taxpayers Association of Oregon, a group that's long advocated against changes to local, or state property taxes.

He said Oregon's limits have put needed constraints on government spending and have been a net positive for taxpayers. And he said many Oregonians probably can't afford to pay taxes on what their property is really worth. Williams thinks most Oregon property-owners appreciate the predictability of the 3% cap.

"Eugene should rather be focusing in on ‘how can we reduce the cost of government?’” he said. “Bring in some turnaround CPA's that help local governments and businesses to find where the waste is and eliminate redundancies, because the cost of government is growing too big in Eugene and Oregon."

Eugene city leaders say they plan to work with the League of Oregon cities to advocate for restructuring the state's property tax system, though any significant changes would require a statewide ballot measure.

In the meantime, they'll focus on their gap: $14 million over the next two years.

Medary said vacant positions, cuts and an increasing wastewater charges will get the city through this year.

"That brings our gap down next year, but we still have a pretty substantial revenue need, or reduction need," she said.

She said Eugene may have to follow the lead of other cities and make up next year’s difference with a fire fee.

The city council will vote on how to fill this year’s budget gap on June 24. It will consider next year’s budget gap in the fall.